Stay updated with the latest news, exclusive insights, and more.

OK OK, he’s not actually mad. But he is a man beset by visions. Today Blackbox sits down with Jordan Fisher, a New-York–born engineer, longtime Japan resident, co-founder of Zehitomo, and a prominent voice in Japan’s evolving startup ecosystem. Jordan reflects on his unconventional path from California student to Japanese finance to entrepreneur, and shares his insights into the structural challenges and opportunities for startups in Japan today.

Sure. I grew up in New York, and growing up I was always passionate about computers and technology. In high school I became fascinated by AI, especially in games, since that was where AI was most applied. So I went to college in California and started studying Japanese on the side. I went to USC, University of Southern California, which had the best video game programming curriculum at the time. We had an AI campus at Marina Del Rey, and so I had a lot of great teachers and people around that time. Over my summers, I first taught video game programming at this kind of summer camp, then between my sophomore and junior year, I went to Asia for the first time. So at that point, I'd been studying Japanese, but I also got really into table tennis… so I went to train in China. And then I came to Japan on the way back

I came back to the States and I was like, "Wow, the food is so bad here and the people are so loud and trains don't run on time. Why did I come back?" And so I thought I wanted to challenge myself in Japan for my next chapter.

So being a computer science grad in California in the 2000s, basically going to Silicon Valley was the done thing. So a lot of my friends went off to work at, you know, the Googles, the Amazons, the Facebooks. I was a weird one that instead decided to move to Japan and work in finance in 2008, when 2008 was a very happening year in finance, if you may remember.

I started off building electronic trading platforms for the fixed income business in Asia. I moved on to more of a quantity role on the rates desk in Japan, which is where we made most of our money from Asia. It was great to sit next to a lot of really talented people and build solutions together, and ended up piloting something that is still now being used by the fixed income business globally at JP Morgan. I had some opportunities to take on some pretty big projects and work really really hard, but loving it because it was a meritocracy, right? You worked hard and you are rewarded for performing well. And not all of Japan necessarily worked like that.

My first daughter was born in 2016, and that's the time that I kind of took a step back, really wanted to cherish that time in life, even though I loved everything I was doing at JP. And I realized that being a salaryman in Japan: trains run on time every day. Sushi tastes great every day. Markets open and close. Things are rational. Clean, safe, everything was wonderful. But outside of that; getting married, having a kid, moving house, things were quite the opposite—they were really inefficient. Society's expectation was that my wife would do a lot of these inefficient things and manage these projects.

So, as an engineer, things that are unfair or inefficient are like my mortal enemies. That's the reason you stay up late to code something even if it would be easier to do it manually. That’s what led me down the path of launching Zehitomo.

Zehitomo is a marketplace for services in Japan. You can hire around 600 different types of services, from a personal trainer to a photographer to renovating your home.

It started off with me and my co-founder bootstrapping, and we ended up bushwhacking through the then-just-emerging startup ecosystem. This was in 2015. VCs in Japan only really started around 2013, and the small IPO was very much the goal.

When you start up a company the goal is to build something massive. And I remember even when we were raising our seed round, we had these investors like, “what is your plan month by month until you go public? What month are you going to go public with exactly how much?” And obviously there's some value in kind of going through a simulation of how you might grow your business. But… at that point we were basically pre-revenue, right?

IPOs aren't bad. Liquidity is important. But the organizational muscles required to go public are very different from the muscles required to achieve triple-digit growth. In Japan, investors often mandate an IPO before a fund’s maturity. So if an investor enters in Year 3 of a fund with seven years left, the startup effectively has four years to get there, since IPO prep itself takes about three.

That means companies sometimes start the IPO process when they have maybe ¥100 million in revenue. That pulls attention away from growth. In many cases, founders know it’s too early but still must “go through the motions.” It’s a huge misalignment of incentives.

In April, when the TSE announced new guidelines requiring a ¥10 billion market cap within five years of listing, I couldn't help but throw up my arms with joy. And again, that's not that large of a a capl, but going from 4 billion after 10 years to, you know, 10 billion in in 5 years, given that 70% of the growth market was under that 10 billion yen line, it will be a great catalyst. It was a strong signal to raise the bar and discourage small IPOs that don’t serve founders or the ecosystem.

Kishida’s five-year plan also helped. People complain the government should “do more,” but they identified 49 specific issues; pretty much everything that was wrong with the ecosystem. And as a founder that had been through it, I was like yeah this is a great list of things that are wrong. Everything from capital, to stock option structures, to M&A. It was a great list, and said clearly: Japan needs startups. The biggest shift is talent: far more students today know what a startup is, compared with even five years ago.

So I maybe I'm I'm jumping around a little bit, but going back to Zehitomo: the first five years was very much chewing glass.You know, learning by failing at things and somehow navigating fundraises and and hiring and building out the team, we scaled it to a bit over 100 employees and raised a total of 3.7 billion yen. So I think my role in the ecosystem has become, like: I was the weird foreign founder that started a very Japanese startup, and I understood the foreign founder mentality but also went deep into the Japanese founder process. This kind of cross-pollinating led me to speak at many events, and, you know, be the one foreigner in a room of hundreds of Japanese founders or investors.

I always enjoyed trying to help bridge that gap, but after I moved from CEO to chairman of Zehitomo, I was thinking “how do I spend my next decade?” I spent eight years at JP Morgan and at that time eight years running and scaling Zehitomo, which was still very much my child—but being chairman feels like I'm like when your child's going to boarding school, right?

We had this 5-year plan and things were moving along, and I realized that actually the onus was very much on the private markets to take advantage of this window and this opportunity to really build out the infrastructure for more globally ambitious founders. And it's not that the existing ecosystem didn't want to do this, but the existing ecosystem knows what it knows, right?

The fact is that, in Japan, 100 companies go public a year. The Japanese ecosystem knows how to facilitate that process. It knows how to grow a SaaS company. It knows how to, you know, find customers, find the best practices for pain points, how to go through the audit process, and get a securities underwriter, and all that.

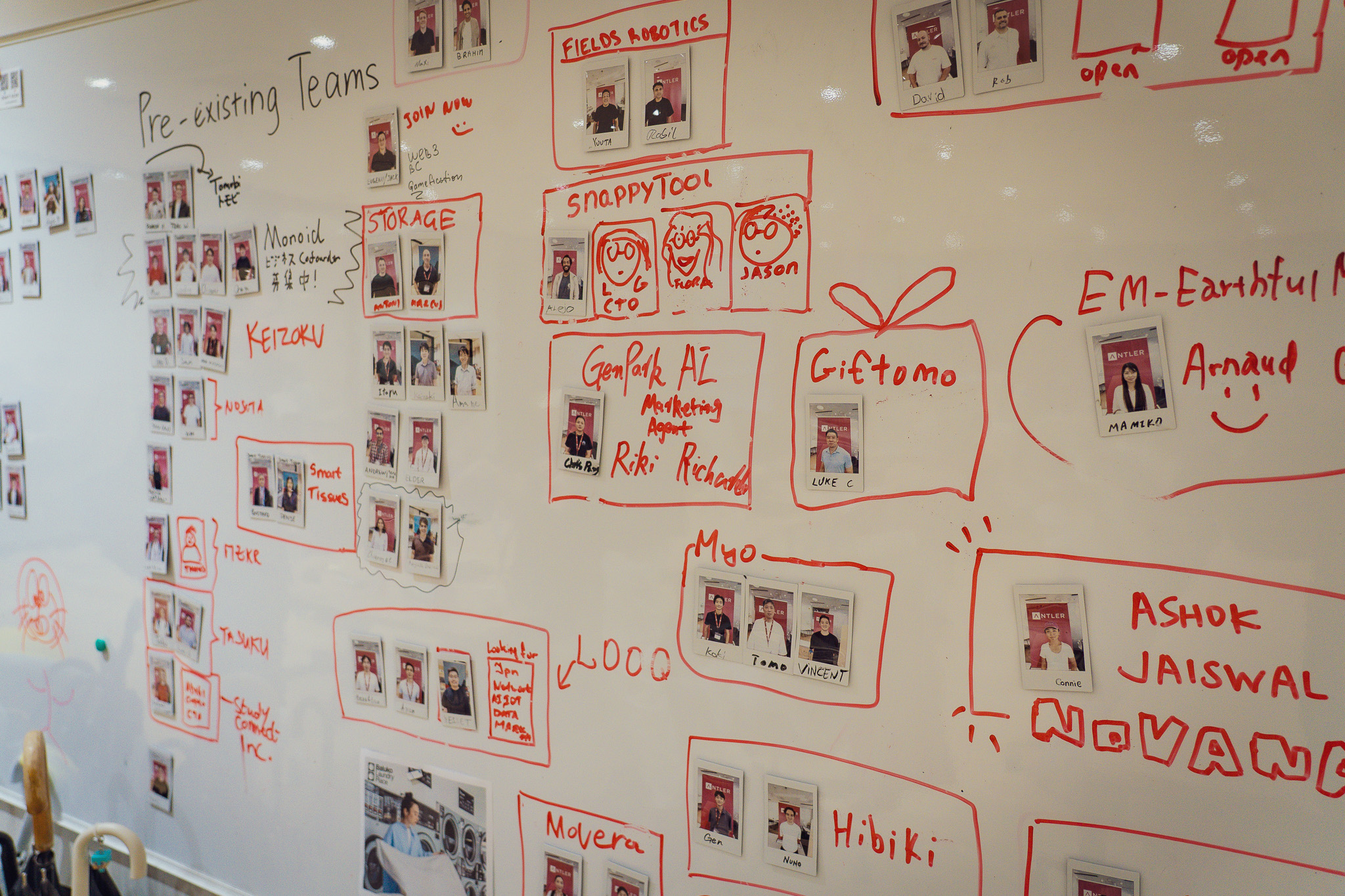

But it doesn't have access to the experience of startup-style founders, and there’s no recourse for new ones to meet similar founders that came before them. And that’s what we seek to redress at Antler: get those guys all together in the same room, give them access to the mentorship and support they need, and let them go for it.

Japan is a very status driven society in a lot of ways. People go to work at the largest company because that gives you status, right? And you can tell your in-laws, “oh yes, I work at Mitsubishi.” And if you were doing a startup, it was like, “oh, I'm sorry to hear that.”

But—going back to the IPO issue—if you're a listed company CEO, then that gives you a seal of approval, and now your in-laws can be proud of you again. You can join the golf clubs et cetera. So I think there was quite a lot of stigma to say, “forget the IPO, we should go out and build unicorns and, dare I say, decacorns.” And even though the government’s Five Year Startup Plan kind of shifted energy in that direction, there weren't many people ready to follow that journey.

Even though there are domestic unicorns, the largest exit that we had in Japan in the last decade or so was Mercari. But even that was a few billion dollars, which is great but we’re trying to create another Sony or Toyota from Japan, right? This is the purpose of the 5-year plan. Japan's economic future requires another Sony or Toyota if we want to have a pension in 30 or 40 years. So how do we create that?

For me, that’s what I’ve set as my north star: how do we create a decacorn from Japan?

A unicorn you can do purely domestically. But a decacorn, by nature, has to be global. When I work with local founders, a lot of times one of the biggest challenges is that they are only benchmarking the other companies in Japan. The global market may exist, and that may be something that we look at later on down the line by just benchmarking the other companies in Japan. Hence, you can only win against the companies in Japan.

Yeah. And so you know what’s going on in Japan, but what about the fastest growing competitors in Silicon Valley or in China or anywhere else in the world? And so when I was running Zehitomo, I connected with the CEOs of companies doing similar businesses in dozens of countries.Our largest competitor was in the US, it was a listed company, a couple billion in revenue, and I was on all their earnings calls, I was talking to their shareholders. I was talking to their leadership. I would talk to employees. I think becoming a subject matter expert and benchmarking against the best players globally, learning from them, sharing, and building those relationships is the one piece that is missing in our ecosystem, and so I always encourage founders in the beginning to do so.

Even if I'm exceeding in Japan, you need to benchmark yourself against global best practices. We have all the ingredients, really talented people in Japan, but how do we create that path for ambitious founders to let them know that, hey: you can go out and you can build and you can raise from global investors; not just any global investor but global investors that have overseen other decacorns.

And we’re starting to see it. Last year, we had a number of big, international investors, Bessemer or Koula for example, make their first investments in Japan. So the investors are there, and are interested; but it's chicken and egg. Companies here have to rise to meet the challenge.