Stay updated with the latest news, exclusive insights, and more.

.png)

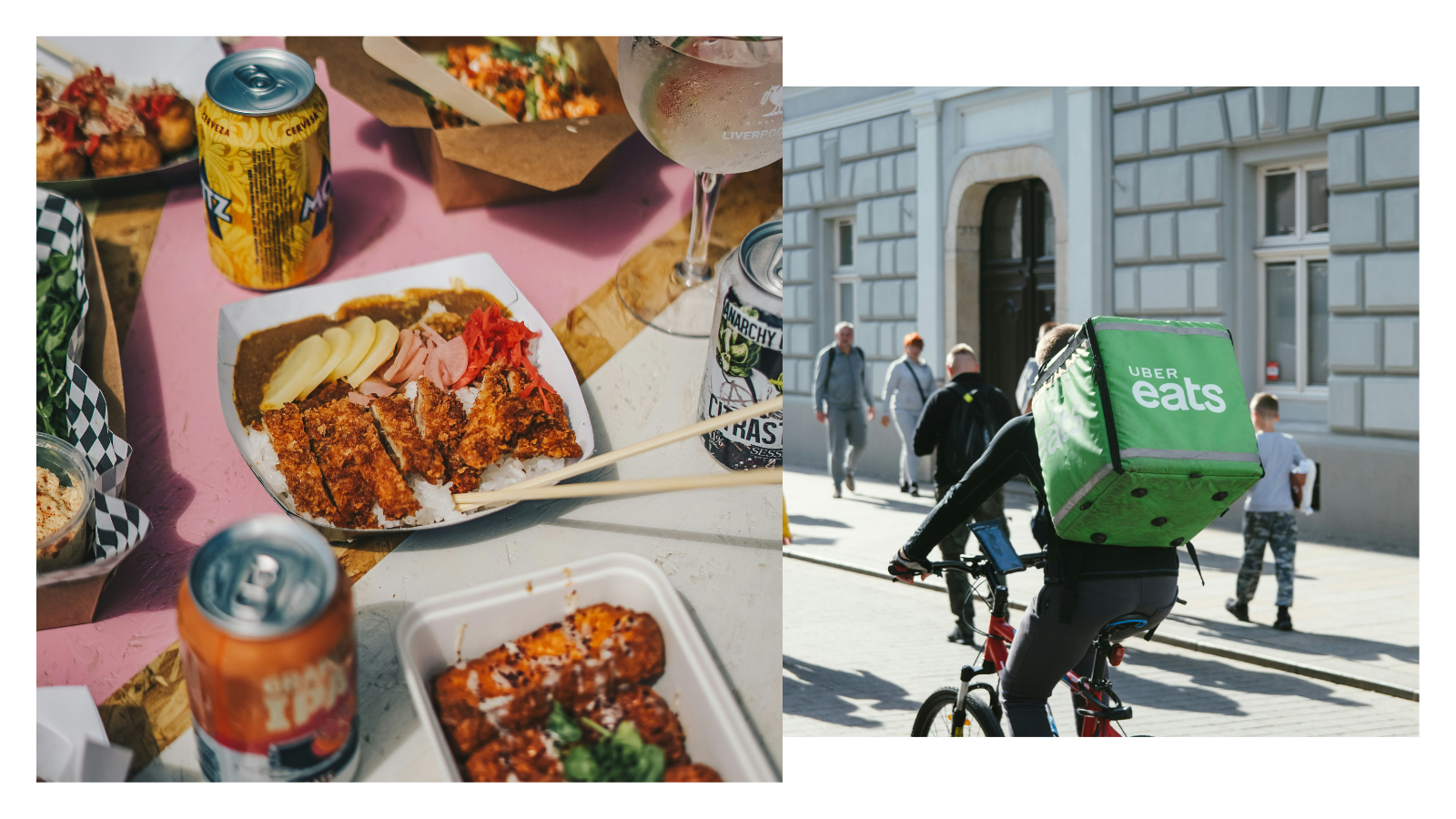

Japan has been enjoying demae - restaurant delivery culture - since the Edo period. Whether it was soba, sushi, or unagi, meals have commonly been offered as delivery; first on foot, then bicycle, then motorbike. Food is delivered on the restaurant’s plates and dishes to be left outside when the customer finishes for later retrieval, a system which can still be commonly seen today. Demae is not just a system of convenience. It is a custom of hospitality, service, presentation, and trust.

Today, Japan’s delivery scene is changing rapidly. Services like Uber Eats, Demaekan, and Wolt have become part of daily life in cities, with an ever-increasing number of new players, platforms, and technologies redefining how food is delivered, including fleet delivery startups and robot couriers. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated this shift and brought both momentum and market shakeups.

In this article, we explore how Japan’s food delivery has evolved through tradition and technology. We look at the digital transformation, cultural context, and what the future may hold. For global entrepreneurs, food-tech innovators, and investors, Japan offers more than just sushi and ramen. It is a real-time case study in delivery innovation.

The History of Demae

During the Edo Period (1603-1868) local restaurants delivered meals such as soba, sushi, tempura, and unagi by hand, with delivery staff carrying stacked wooden boxes on their shoulders, and later, bicycles.

Demae was more than just a service. It reflected Japanese values like omotenashi, meaning wholehearted hospitality and attention to presentation. Meals were carefully prepared and arranged to maintain taste and appearance. The delivery experience helped build strong relationships between restaurants and their local communities.

In the Showa Era (1926-1989), urbanization and changes in lifestyle made food delivery even more important. Restaurants continued to provide their own delivery services. Starting in the 1970s and 1980s, food brand chains including pizza shops and Chinese restaurants began to introduce standardized delivery systems. These chains combined traditional demae with greater efficiency and branding. Uniformed delivery drivers, branded scooters, and insulated containers became common.

By the time the Heisei Era started in 1989, food delivery was a common convenience supported by telephone orders and paper flyers. Japan’s food delivery culture began not with technology but with a deep-rooted commitment to care, quality, and trust within local communities.

.png)

Transition to Online Food Delivery Services

The wave of online food delivery in Japan began gradually in the 2010s and then accelerated during the COVID-19 pandemic. Before smartphones and apps became mainstream, most delivery orders were made by phone call. Restaurants often handled delivery themselves, especially longstanding shops like soba or sushi restaurants.

Before that, it was Demaekan. in 1999, Demaekan launched as one of Japan’s first online food delivery platforms, connecting users with local restaurants. It helped digitalize the traditional order system before food delivery apps. Then, technology began to transform the market.

Uber Eats entered Japan in 2016, starting in Tokyo. The idea of freelance couriers delivering food from various restaurants was unfamiliar at first. However, younger consumers, especially in big cities, quickly embraced the service. Long-established domestic giant Demaekan was its major competitor, but other domestic and external players like Wolt, Foodpanda, Chompy, Foodneko, and Didi Food swiftly entered the market. The pandemic caused a massive surge in demand, with all food delivery platforms, large and small, fighting for market share. Some succeeded, while others flopped.

By 2021, food delivery had become a regular part of daily life for millions of people. Apps made it easy to order from restaurants that had never offered delivery before. For restaurants, it became a lifeline during lockdowns and restrictions. In 2024, Japan’s food delivery market reached 796.7 billion yen (approx. 5.1 billion USD). Although this is a 7.6% decrease from the previous year, it still represents a 90.5% increase compared to pre-pandemic levels. Uber Eats holds the largest market share at 57.3%, followed by Demaekan at 36.4%, with Wolt, menu, and others making up the rest.

The Other Side of the Delivery Ecosystem

As food delivery grows, a new wave of platforms is emerging to support the ecosystem and connect delivery operation more efficiently.

Aggregator platforms such as Orderly, Camel, and Ordee help restaurants manage multiple delivery apps from a single interface. These services often integrate POS systems, enabling smoother order processing and reducing operational stress in busy kitchens.

On the logistics side, specialized delivery providers like AnyCarry and Hacobell have entered the market. These companies offer flexible solutions for delivery platforms. While Uber Eats uses freelance drivers, logistics providers enable more stable and reliable delivery services

Japan’s delivery landscape has also expanded beyond restaurants. Companies like Onigo and Korea’s Coupang focus on what are known as "dark store." These stores are not open to walk-in customers and exist only to fulfill rapid delivery orders for groceries, alcohol, and everyday essentials.

Together, these companies represent a shift in Japan’s food delivery culture toward a more complex and tech-enabled ecosystem, serving not only restaurants and consumers, but also retailers seeking fast and flexible delivery channels.

Japan’s food delivery market continues to evolve, driven by innovation. Companies like Panasonic, ZMP, and Cartken (with Uber Eats Japan) are testing autonomous delivery robots, while others are developing sustainable packaging to reduce environmental impact.

Looking ahead, Japan faces extreme examples of global challenges, like ultradense urban logistics and a shrinking workforce. With its rich food culture and fast tech adoption, Japan remains a valuable testbed for the future of food delivery.